It’s not every day that you see a scientist create a work of art. But for the third annual Agar Art contest hosted by the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), talented microbiologists from around the world flexed their creative muscles to create intricate, ethereal paintings. Only, instead of using canvas and paint, they relied on strains of yeast, microbial bacteria, and agar plates. And what they created might cause you to rethink everything you ever thought about mold.

For those uninitiated in the mediums of microbiology, agar plates are simply petri dishes containing a thin layer of the gelatinous substance agar. Chock-full of sugar and nutrients, the agar provides a controlled, stable environment in which bacteria can grow. Scientists can then observe that growth through microscopes, allowing them to test the effectiveness of disinfectants, antibiotics, and other antibacterials.

Though the Agar Art contest wasn’t so much about preventing bacteria growth as it was channeling that growth into microbial masterpieces. Take a look at the three winners to see what I mean.

First place: “Sunset at the End” by Jasmine Temple

Microbiologist Jasmine Temple took the first-place prize with a summery sunset “painting” she created by printing tiny droplets of baker’s yeast onto an agar plate. Temple, who works as a lab technician at NYU’s Langone Medical Center, said she was inspired by a time she watched the sun set over Montauk. “I was struck by the beauty of the sunset and I thought of how beautiful it would be in the pink, blue, and purple yeast strains,” she told ASM.

Having double majored in biology and studio art as an undergrad, Temple says agar art seemed like a good way to combine both of those interests. But it was a paper postdoctoral fellow Leslie Mitchell published in 2015 about pathway assembly in yeast that really jump-started her experimentation with the unusual art form. “Two of the pathways she assembled were beta-carotene and violacien,” Temple tells GOOD. “She found that the depending on how the pathways were expressed, they yielded different colors; pinks, oranges, and yellows for the beta-carotene, and black, purples, and grays for the violacien.”

In this way, Temple is able to match an image’s color values with the colors expressed by different pathways of yeast. As Temple explains,

“I draw the image on a tablet, put it through an algorithm that matches the color values of the image I drew to the color values of the yeast we have. The algorithm gives me a kind of map that I can give with the correct pigments to a machine called an acoustic liquid handler. The machine will then print out the map with the yeast, giving tiny pinhead sized droplets that grow into the image.”

While this method requires a bit of training as well as a background in biology, Temple says anyone can be trained to make agar art using her specific process. And while we typically think of yeast as a means to make our favorite fermented products like bread and beer, Temple wants to point out you can also use yeast to make biofuel, vitamins, and pharmaceuticals.

Second place: “Finding Pneumo” by Linh Ngo

Second-place winner Linh Ngo, who works as a microbiology technologist in Ontario, told ASM her children’s love of the movie Finding Nemo inspired her microbial painting of coral. In the process, she learned about the disastrous consequences global warming poses to coral reefs. “It started as a project where I could bridge my creative side with my microbiology skills,” she told ASM, “but [it] ended up bringing awareness to the coral reefs.”

Though this wouldn’t be Ngo’s first attempt at painting with microbes. She started getting creative with control samples to entertain her coworkers, and eventually drew everything from the Toronto Blue Jays mascot to the character Olaf from Frozen. “I had a colleague ask me to draw her a minion,” Ngo tells GOOD, adding, “There really is no inspiration, I just love to draw.”

But don’t go painting your living room with bacteria just yet. As Ngo stressed to GOOD, the types of bacteria she and her coworkers use on a daily basis are not safe to handle outside of a structured lab environment. She added that, “It's important to have the knowledge of pathogens and their associated risks.” For instance, to get a textured look for her coral, Ngo used Candida tropicalis, a pathogenic strain of yeast that can cause fungal infections when mishandled.

Third place: “Dancing Microbes” by Ana Tsitsishvili

Undergraduate student Ana Tsitsishvili from Tbilisi, Georgia, drew a romantic fairytale painting largely using Staphylococcus epidermidis, which can be found naturally on our skin, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, a “common environmental inhabitant.” It was at the Agricultural University of Georgia that Tsitsishvili first encountered Rhodotorula mucilaginosa’s vibrant red microbes growing on a petri dish. With the encouragement of her professor, Giorgi Melashvili, Tsitsishvili began collecting samples to create a palette of different colored microbes.

According to Tsitsishvili, microbiologists have identified 1,500 species of yeast so far. These single-celled microorganisms date back hundreds of millions of years, making for some truly ancient art supplies.

Tsitsishvili was kind enough to pass along photos of her other microbial masterpieces, which you can view below. Truly, entire worlds exist beyond what the eye can see.

To see more of Tsitsishvili’s work and paintings by competitors who didn’t place this year, check out the slideshow above. Truly, a vast world exists beyond what the eye can see.

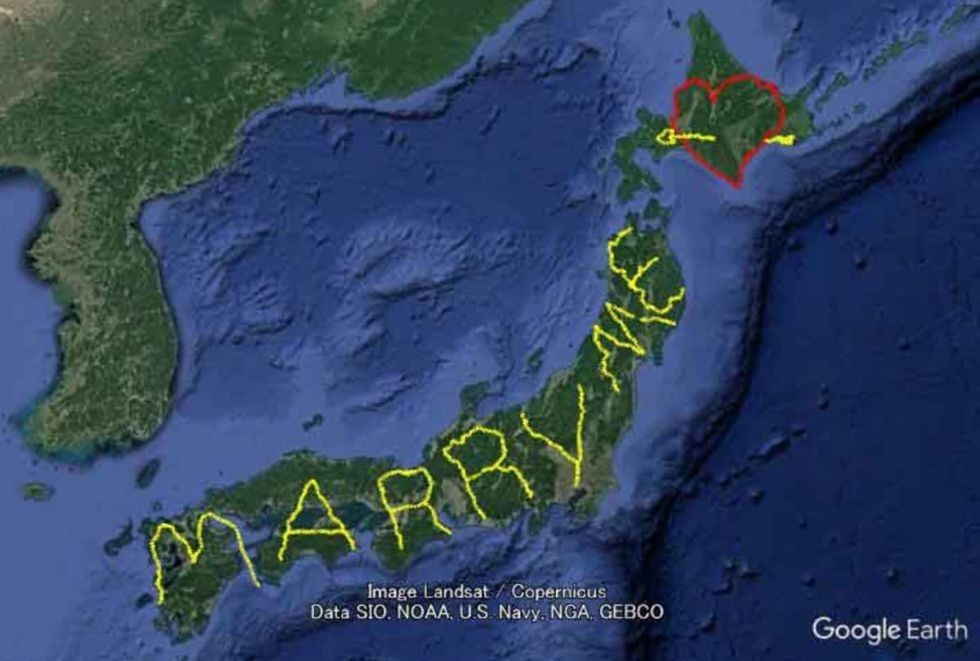

Yassan's GPS Drawing Project

Yassan's GPS Drawing Project

Elon Musk poses for a photo op.

Elon Musk poses for a photo op.

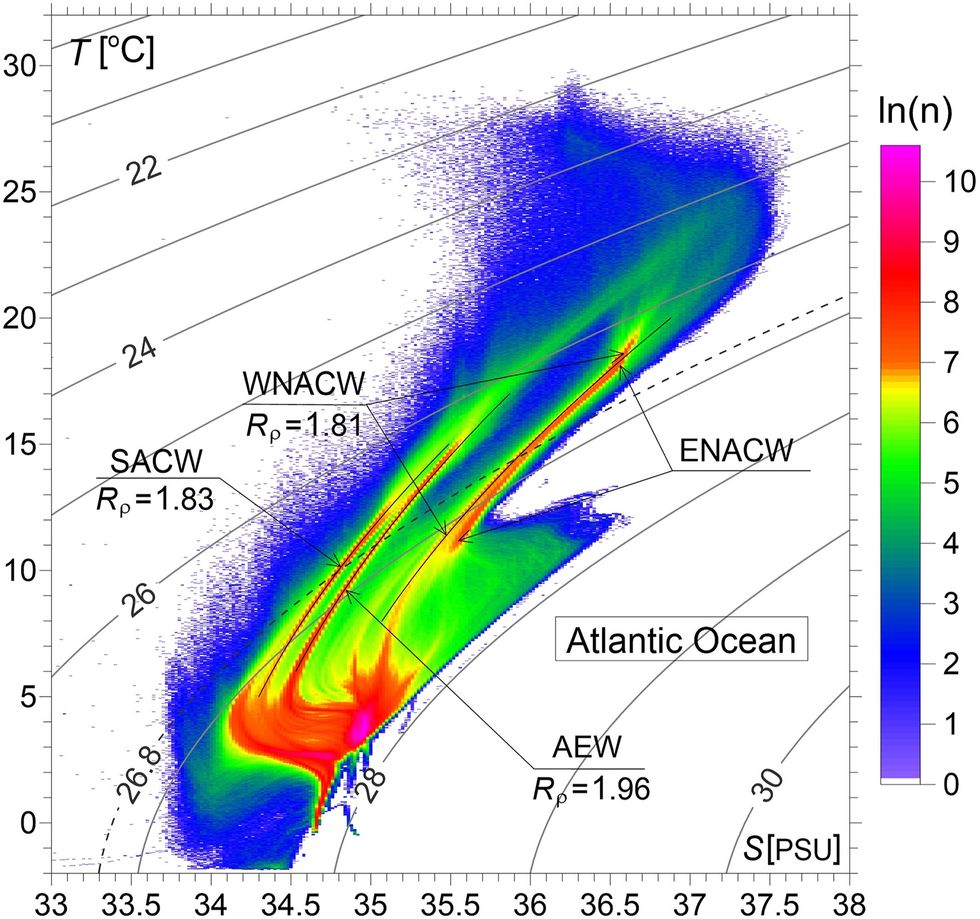

The Atlantic Ocean still holds secrets that scientists are hunting down.

The Atlantic Ocean still holds secrets that scientists are hunting down.  A detailed map was made using temperature and salinity profiles from the Argo data repository.

A detailed map was made using temperature and salinity profiles from the Argo data repository. Though you might not be able to tell one bit of water from another, scientists can and there are real consequences for the planet.

Though you might not be able to tell one bit of water from another, scientists can and there are real consequences for the planet.

Prepping the pieCanva

Prepping the pieCanva Pepperoni sliceCanva

Pepperoni sliceCanva Pizza partyCanva

Pizza partyCanva

Cozy pizzaCanva

Cozy pizzaCanva

Making the pie from scratchCanva

Making the pie from scratchCanva Image Source: Reddit I

Image Source: Reddit I  Image Source: Reddit I

Image Source: Reddit I