I moved to New York August 27, 2001 to attend NYU for grad school. I was 22. I had never kept a diary before, but moving to New York for the first time seemed like a good excuse to start. In the entries leading up to the one recorded here, I wrote about trips to IKEA and confusing the sounds of the subway with thunder. I wrote about my too-loud upstairs neighbor and a dead ladybug on my windowsill. I wrote about a man named Dukes I met on the subway who dreams about people chasing him down the street and shooting his legs, about Kate Winslet’s divorce and eating too much Cherry Garcia and buying my first cellphone. The contrast of the entries leading up to September 11th and September 11th itself is eerie and sad. Every mundane detail—the thundering subway, the dead ladybug—seems bestowed with meaning, as if they were not, in fact, mundane details, but portents of things to come.

But, of course, they weren’t.

Sept. 11

Yeah well, the date’s slightly bigger, slightly neater, because it’s important. Set the alarm for 8:45. Had a weird dream with morbid and mystical themes—went back to it after the beeping.

Then I heard a sound like a plane veering high-pitched through the atmosphere and colliding into the side of a building. I got up. My roommates—well, Meg and Jesse—were at the at the breakfast table, coffee in their hands. Hey—I said—did you guys hear that? What the fuck was that? And Jesse said—yeah, I was like, uh, a plane just crashed. We laughed and finished our coffee.

Meg told me Keri found a mouse in one of her sticky traps. Kinda half inside her laundry basket. What’ll happen to the mouse? I asked. And Meg said—you know, whatever. If they kill it—fine. If they release it into some field—fine. And then we watched the painter roll layers of white onto Keri’s walls. I blow-dried my hair and Meg left for work.

15 minutes later she runs back into the apartment and it’s the most horrifying thing, she says.

A plane crashed into the side of the World Trade Center. It’s on fire, she says. So I run outside in my socks - a gesture I thought typically melodramatic - ‘cause I’m such a cheese. But then I saw them through the arch. Slim and grey and tall—with that straight glint of sky slicing them apart—and then a billow of smoke storming around their peaks—white as it blew to the left, heavy and black as it spilled to the right. A stripe of bright orange fire tied around one floor like a ribbon.

I stood there in my jeans, my checked tank with the ribbon around the ribcage—in my socks. I couldn’t believe it was actually an occasion for it. That this was worse than melodrama. And I ran back for the phone. I called Mark and left a message and my voice quivered and I used the word “disturbing.” And I thought—too much. But then a flash of light flicked through the room. And there was another hijacked plane. And then a tower fell.

I took pictures—I didn’t think myself the type—but: Washington Square Park, a flourish of foliage, a cross to the left, construction to the right, and half the World Trade Center above, flaming like a torch, like a tacky electric church candle.

I watched it with my hand over my mouth. And some guy teetered around on a bicycle, in a fatigue jacket, ranting about judgment. A woman told him to shut up before someone fucking killed him. Then I listen to some men narrate the event—convince each other that the other “building’s going down,” and announce every moment “another cat jumped out the window.” I watched them, too—one little black dot after another, falling along the sky like dust rolling down a wall, and I couldn’t believe they were people with lives, with families, with anxieties, and regular everyday choices to make—and suddenly they’re forced to choose between jumping out the window of the 110th floor of a tower or staying inside. And they were in a situation where jumping, where falling 110 stories, was the wisest choice. It was inconceivable. It was nauseating. And I knew the ways I reacted to this—whichever emotion swept me over or commentary that emotion elicited—ultimately they were tainted. Tainted by my luck—neither deserved or undeserved.

Tainted by the fact that, in a relative sense, I had no right to act important. And that anyone alive right now was pathetic and insignificant and full of the movieishness of it all.

The rest of the day was full of adrenaline and laughter and junk food and beer and then numbness and a feeling of walking through something thick, like mud.

The sirens continue. Bart told me I was smart and funny and pretty. “The beer and the building,” he said. And I agreed. But it’s not true. Everyday things motivated that speech.

Do everyday things motivate everything? Is that a cheesy question or does the very un-everydayness of today allow it? Is that a contradiction? What can I do to deal with this? Am I really asking why? I mean, why is there so much pain and misery in the world? Am I fucking asking that?

All my furniture is crammed into the middle of my room. It’s like that early morning of that big earthquake in LA—when my bed and desk and bureau shifted and shimmied into a huddle. This time I pushed them together myself. They paint the walls white tomorrow and I have to make things easier.

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

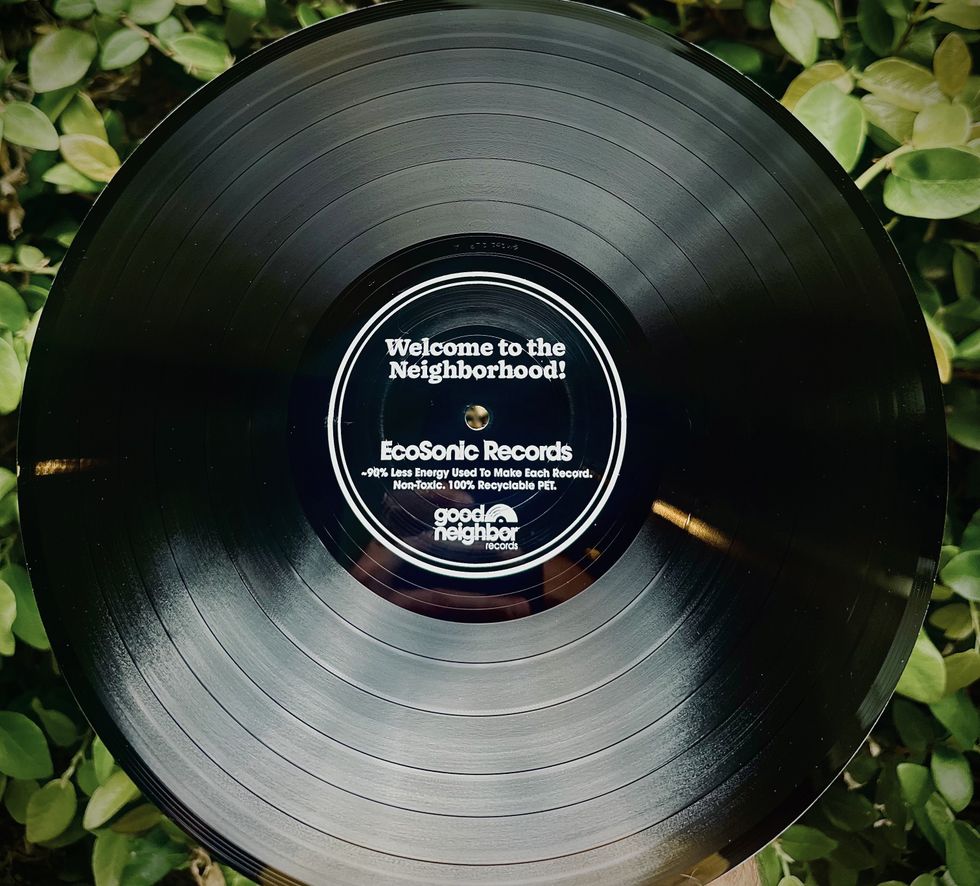

Good Neighbor record.Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Good Neighbor record.Photo credit: Good Neighbor Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Photo credit: Good Neighbor Good Neighbor Records are green.Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Good Neighbor Records are green.Photo credit: Good Neighbor