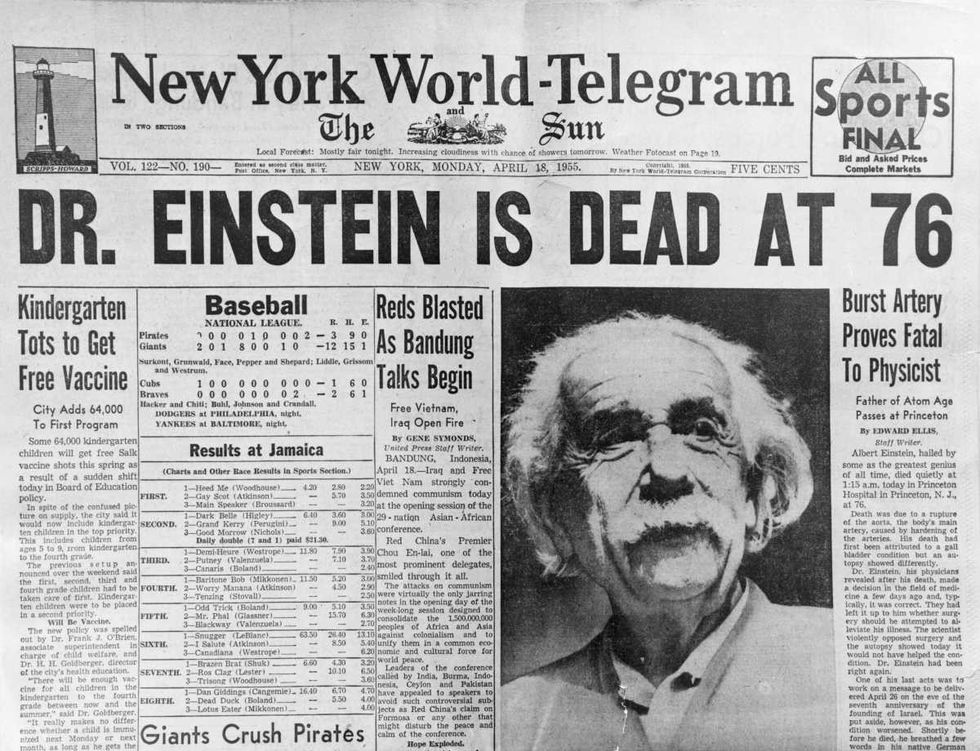

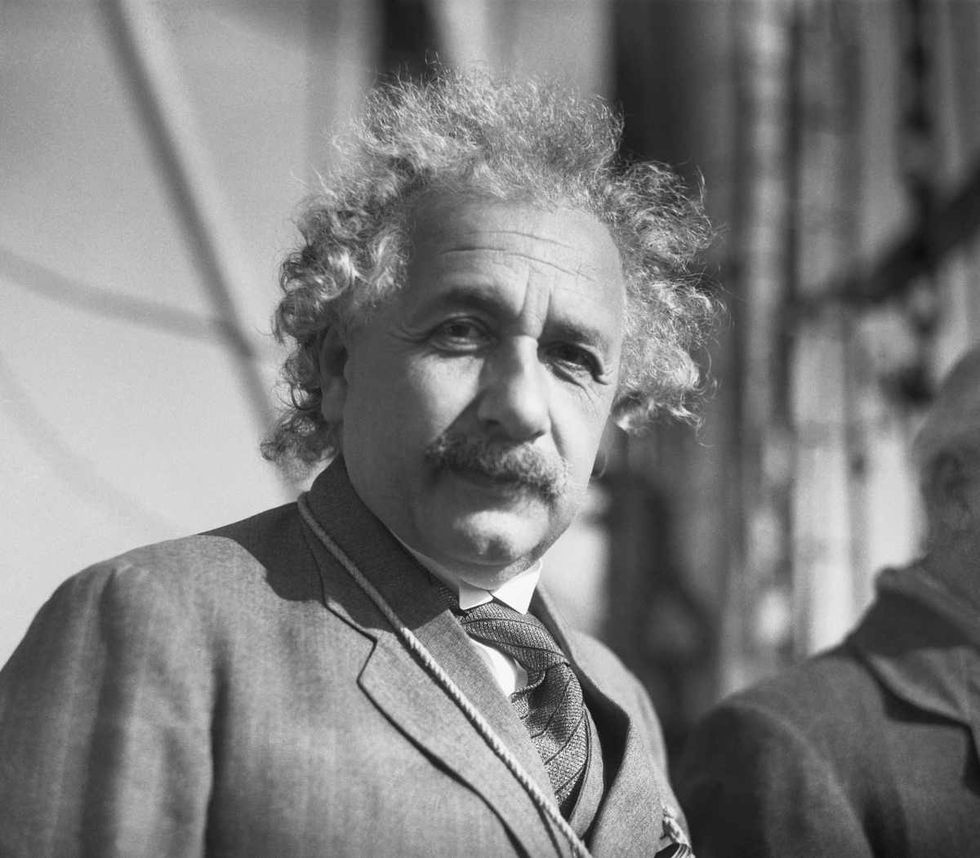

When Albert Einstein was 12, a “sacred little geometry book” ignited his curiosity about science and mathematics. As an adult, he answered letters, wrote poems, played the violin, and constantly pondered scientific theories. This passion for science didn’t end with his death. On April 18, 1955, Einstein died of heart failure in Princeton Hospital at 76. Intriguingly, when his body was cremated, his brain was missing. PBS reported that a man had secretly removed it. Years later, scientists who got the chance to study his brain discovered it had unique features that may have given him an edge in cognitive processing.

After the Nobel Prize-winning physicist passed away, Chief Pathologist Thomas Harvey at Princeton Hospital conducted Einstein’s autopsy. Without the family's permission, Harvey quietly removed Einstein’s brain for future research. He cut it into 240 pieces, stored them in mason jars, and preserved them in celloidin.

Many scientists believed that Harvey’s actions were clandestine. In his book “Postcards from the Brain Museum,” Brian Burrell wrote that Harvey was simply a pathologist who did autopsies, and he was not appropriately suited for carrying out any such research. “It should be emphasized that Thomas Harvey was not a brain specialist. His understanding of the brain did not extend beyond the postmortem diagnosis of disease, atrophy, or injury. Which is to say that he had neither the means nor the expertise to undertake the study he had proposed to Einstein’s son.”

As news of Einstein’s stolen brain spread, the journal Science interviewed Harvey. Neuroanatomist Marian Diamond from the University of California, Berkeley, requested brain samples. Harvey sent her four sugar-cube-sized pieces preserved in chemicals inside a repurposed Miracle Whip jar, according to IFLScience. Finally, scientists had material to study.

In 1985, Diamond published a paper in Experimental Neurology stating that one of the four brain samples had more glial cells for every neuron. Glial cells are types of cells that surround neurons, keeping them alive and covering them with a protective myelin sheath. Another study from 1996 at the University of Alabama revealed that the neurons in Einstein’s brain were tightly packed, allowing, perhaps, for faster processing of information. In a 1999 Lancet paper, Sandra Witelson from McMaster University in Canada studied Harvey's original photographs of Einstein's brain. She said that Einstein's inferior parietal lobule, the part of the brain responsible for spatial cognition and mathematical thought, was wider than normal.

Frederick Lepore reported in his 2018 book, “Finding Einstein’s Brain,” that the dissected brain was returned to the Einstein family, who donated it to the Mütter Medical Museum in Philadelphia. A CBC documentary called “The Man Who Stole Einstein's Brain” followed the journey of the physicist’s brain.

Currently, the curio of the enigmatic brain is in possession of Elliot Kraus, chief pathologist at the University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro, according to BBC. Although rumors are there that Krauss doesn’t allow the brain to be investigated by any scientist, he denies this claim. "I think I am waiting till someone comes with a really good proposal on the material, but I would have to be comfortable that they're not looking at it just to have some, and the notoriety of possessing some," said Krauss. "There has to be a real good scientific reason for having it."

Amid all this, Harvey lost his medical license for purloining the great scientist’s brain. Soon after this, he was seen working in a plastics factory to pay his bills. He died in 2007.

A pair of scissors.

A pair of scissors. A can opener opening a tin can.

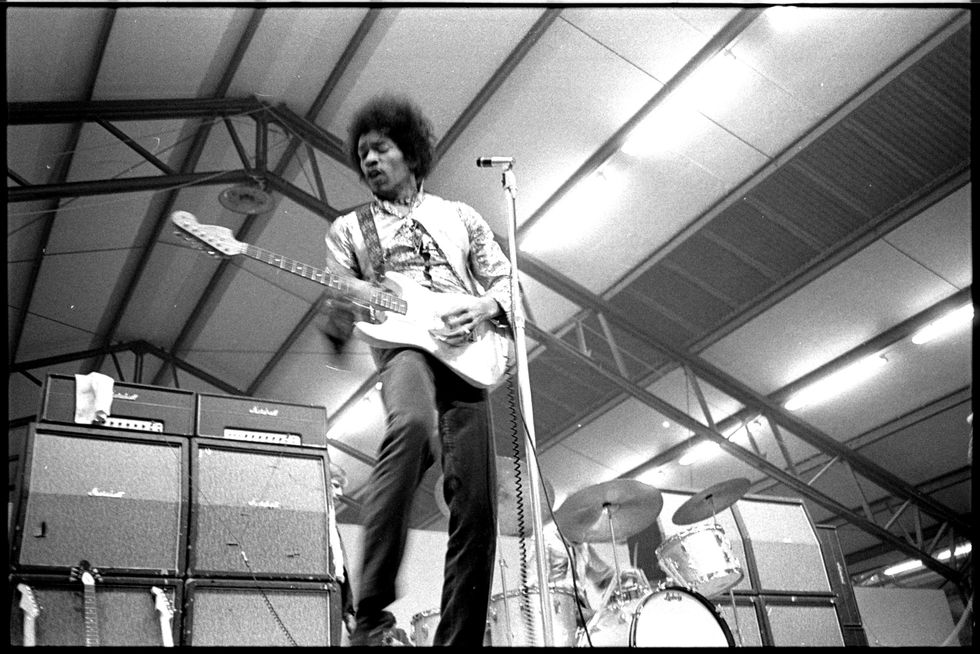

A can opener opening a tin can. Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain

Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain A man handing over $20 in cash.

A man handing over $20 in cash. A person using a power saw.

A person using a power saw.

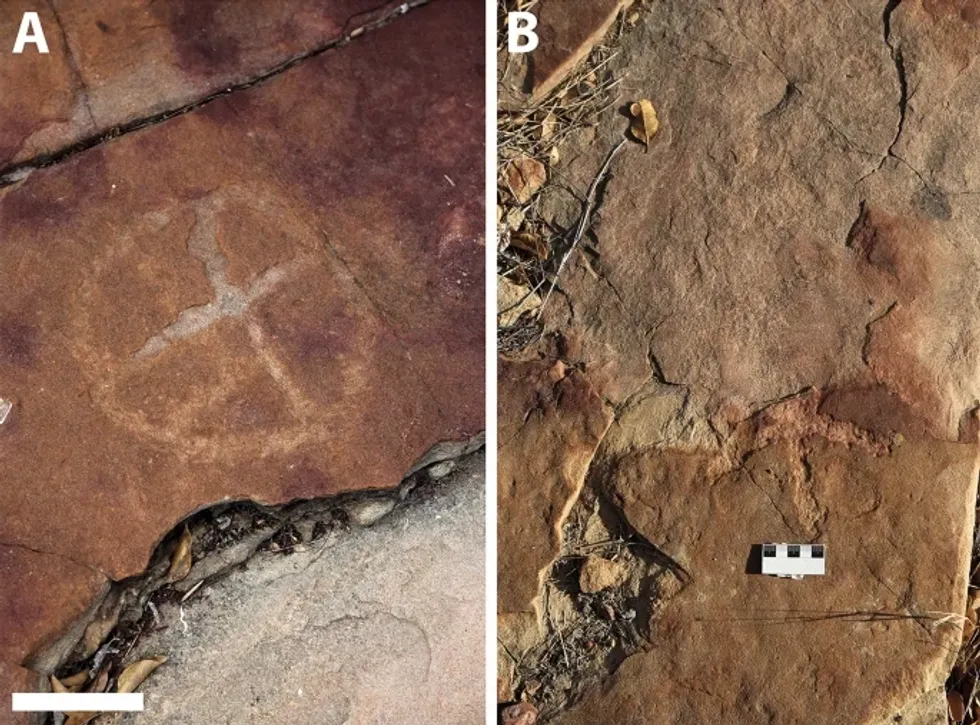

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

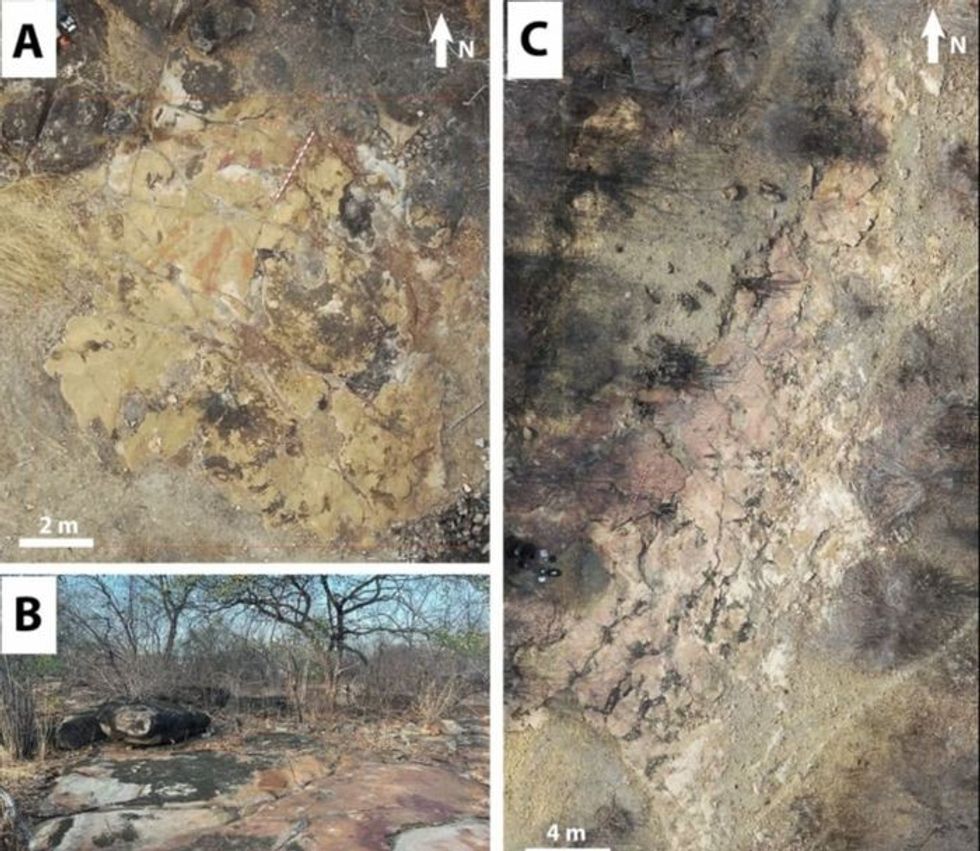

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.