May 15, 1918 was the most painful day of Henry Johnson’s life. It’s also the day he became a war hero applauded by his fellow soldiers, his community, and United States Presidents. On that day, the young soldier ordered to do grunt work due to the color of skin successfully fended off over 20 enemy soldiers by himself.

Sergeant William Henry Johnson was born around July 12, 1892 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, but, due to inconsistencies of record-keeping, he could have been born as early as 1887 or as late as 1897. As a teenager, he moved to New York where he worked as a chauffeur, soda mixer, laborer at a coal mine, and a porter at Albany Union Station before enlisting to the U.S. Army on June 5, 1917, two months after America entered World War I.

Johnson was a private and assigned to Company C, 15th New York Infantry Regiment, a segregated African American unit. Many Black soldiers at the time were sent to do mostly grunt work such as unloading trucks and digging latrines. Given that Johnson stood at a whopping 5’4” tall and weighed 130 lbs., it is safe to assume that not much was expected of him regarding combat. After months of training, he and his regiment, renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment, part of the segregated 93d Infantry Division, was deployed to Europe. After being taught enough French to understand orders, the 369th Infantry was sent to bolster France’s 161st division on April 8, 1918 to help protect the country’s Argonne Forest region.

About 2:00 A.M. on May 15, Johnson and his partner Pvt. Needham Roberts were patrolling a bridge nearby when they heard clipping sounds. Suspecting the clipping noise was the sound of German soldiers cutting fencing around the perimeter, Johnson ordered Roberts to get reinforcements as he lobbed a grenade in the general area of the noise to root out any enemy forces. The enemy returned fire. Reportedly, Roberts immediately ran back to assist Johnson, but was wounded by enemy grenade shrapnel. Johnson was left to fight on his own.

Roberts supplied Johnson with grenades as Johnson returned fire against the enemy, suffering bullet wounds to his hand, side, and head. After running out of ammunition, Johnson accidentally jammed his French rifle after trying to reload it with ammo meant for American weaponry. Using his rifle like a club in one hand and wielding a bolo knife with the other, Johnson charged into the fray and engaged in face-to-face combat. In the midst of the fight, he saw two of the German soldiers attempt to capture Roberts but intercepted them. Johnson would swing, stab, slash, and club whomever came into his path, regardless of the additional bullets that struck him.

Johnson fought the swarm of German soldiers for an hour before reinforcements arrived.

Once his allies appeared, the surviving German soldiers retreated, many of them wounded. Johnson killed four men and suffered 21 wounds. According to different reports from his comrades and official documents, Johnson fought up to 36 men by himself and lived.

The spirited yet skinny Johnson was praised by his peers, with them calling the altercation “The Battle of Henry Johnson” and nicknaming him “Black Death.” He received official recognition and honors as well from the French military, becoming one of the first Americans to be awarded the French Croix de Guerre avec Palme, France's highest award for valor. He and other members of the 369th Infantry, now dubbed the “Harlem Hellfighters,” got a hero’s welcome and celebration in the form of a parade through New York City in February 1919. Teddy Roosevelt even said Johnson was one of the five bravest Americans to serve during the war.

- YouTubeyoutu.be

The military was quick to use Johnson’s bravery and image as recruitment materials, especially when America had to fight again in World War II. However, the multiple wounds and injuries Johnson sustained forced him to discharge from the army. His discharge papers didn’t mention his injuries nor the bravery he displayed. He was forced to return to his job as a porter in Albany, struggling to make ends meet as his injuries made it incredibly difficult to work and maintain employment. He passed away on July 1, 1929 due to myocarditis while living in Washington, D.C. His remains are currently buried in Arlington Cemetery.

Decades later, Johnson would receive multiple posthumous honors. In 1996, President Bill Clinton gave Johnson a long overdue Purple Heart for his service. The U.S. Army awarded Johnson the Distinguished Service Cross in 2002. On June 2, 2015, President Barack Obama gave Johnson the Medal of Honor.

While Johnson wasn’t given his proper honors while alive, his memory and inspirational story lives on. It is important to recognize our heroes while we have them and let them know they are appreciated and worthy before we recognize and honor them upon their passing.

Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child

Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child  Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child

Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child

Speaking in public is still one the most common fears among people.Photo credit: Canva

Speaking in public is still one the most common fears among people.Photo credit: Canva muhammad ali quote GIF by SoulPancake

muhammad ali quote GIF by SoulPancake

Let us all bow before Gary, the Internet's most adventurous feline. Photo credit: James Eastham

Let us all bow before Gary, the Internet's most adventurous feline. Photo credit: James Eastham Gary the Cat enjoys some paddling. Photo credit: James Eastham

Gary the Cat enjoys some paddling. Photo credit: James Eastham James and Gary chat with Ryan Reed and Tony Photo credit: Ryan Reed

James and Gary chat with Ryan Reed and Tony Photo credit: Ryan Reed

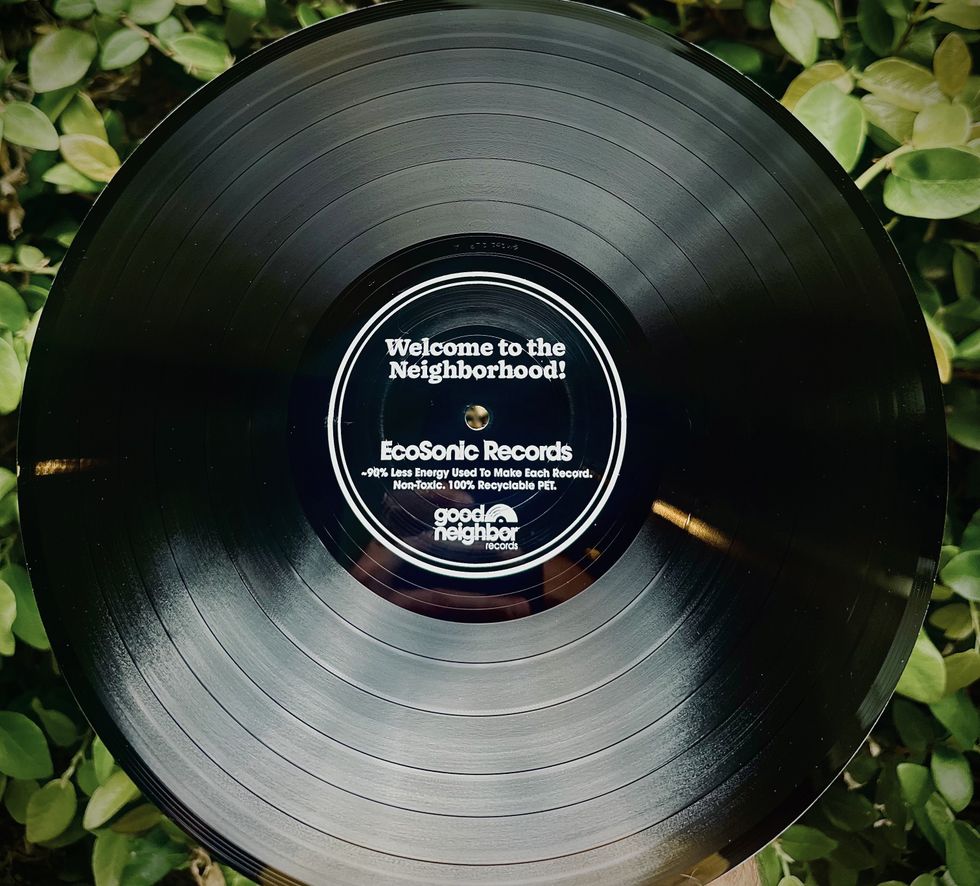

Good Neighbor record.Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Good Neighbor record.Photo credit: Good Neighbor Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Photo credit: Good Neighbor Good Neighbor Records are green.Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Good Neighbor Records are green.Photo credit: Good Neighbor