In the summer of 2024, Carme Rissech, a researcher at Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV), examined skeletal remains from the medieval Spanish fortress, Zorita de los Canes. Part of the MONBONES project, Rissech typically studied the diet and lifestyle of Middle Age monasteries. However, discovering that these remains belonged to Calatrava knights sparked her fascination. Upon detailed investigation, Rissech made a stunning discovery: one set of bones suggested a woman fought as a warrior among the cavalry. The study was published in Scientific Reports.

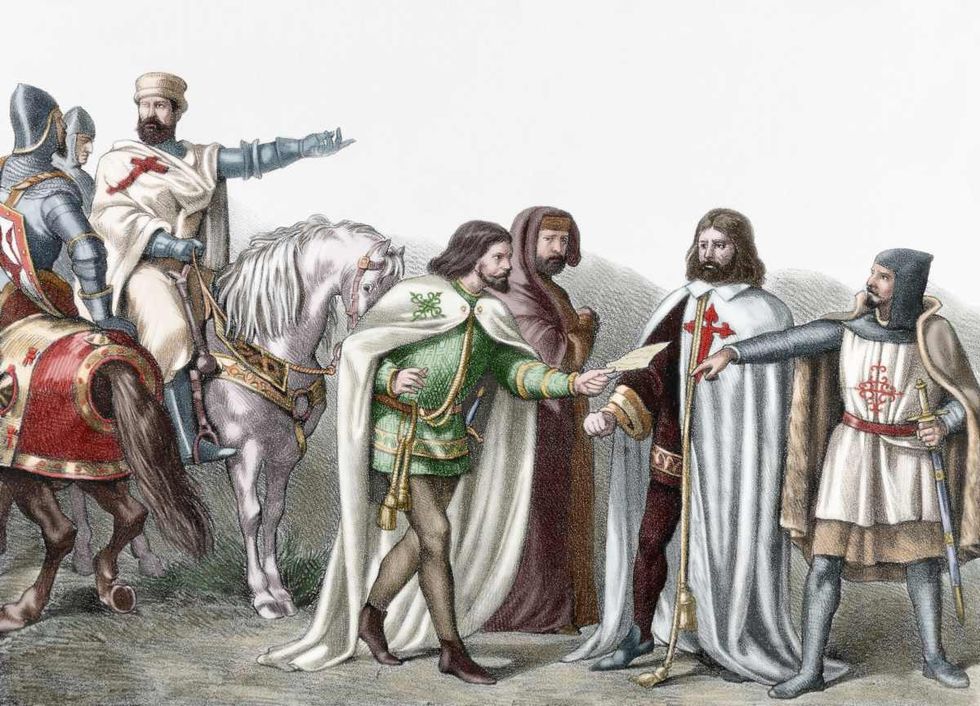

Overlooking the village of Zorita de los Canes and the Tagus River, Zorita Castle is one of Guadalajara’s most majestic Muslim castles. Its history is tied to the Order of Calatrava, a military and religious group dedicated to defending the border from Moorish incursions.

Between the 3rd and 15th centuries, the castle switched its kings, sometimes falling in the hands of Christians, and sometimes Muslims. It was 1124 when it was definitively conquered by the knights of the Order of the Temple. This research led by URV and the Max Planck Institute focused on the diet, lifestyle and causes of death of these medieval religious knights.

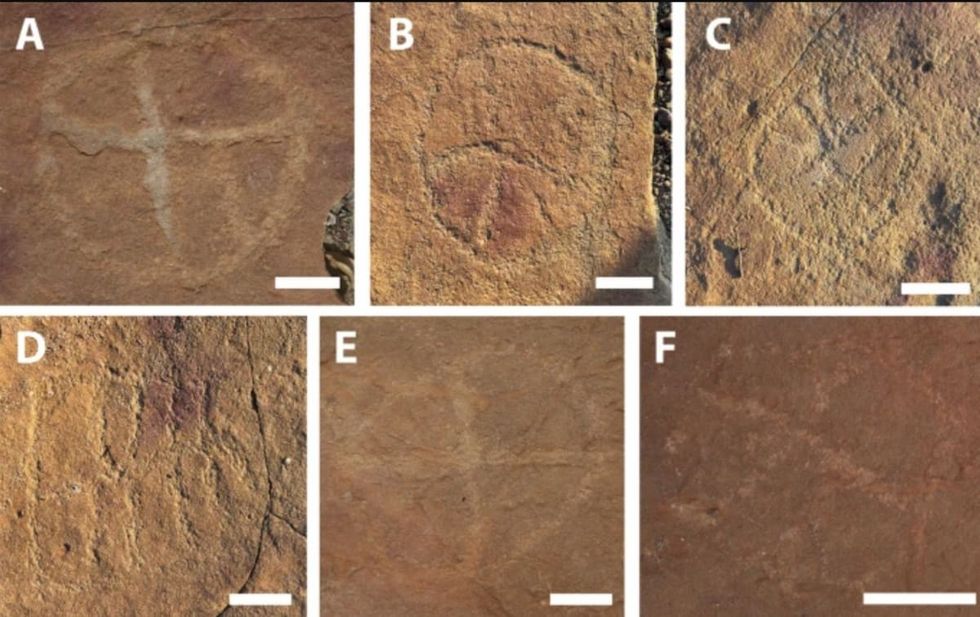

Researchers analyzed the remains of 25 individuals in the castle’s church cemetery, where Calatrava knights were buried between the 12th and 15th centuries. Among the bodies, 23 were monk warriors, one was an infant, and one, surprisingly, was a woman. They identified her as a woman by studying her pelvis bone.

This indicated that a woman who was buried alongside these Calatrava monk warriors, probably fought a battle, and therefore, was a mighty knight. "I believe that these remains belong to a female warrior. We should picture her as a warrior of about forty years of age, just under five feet tall, neither stocky nor slender, and skillful with a sword," Rissech said, as per URV. They also hypothesized that the woman was most likely the mother of the infant whose remains were unearthed among the warriors' skeletons.

The study also revealed that many of the skeletons displayed features that provided clues to violent, even mortal wounds, including a "significant number of penetrating stab wounds and blunt force injuries," on the skulls and pelvic areas, likely received in battle. "It is clear that they died in battle," Patxi Pérez-Ramallo, an archaeologist and author of the study at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, told Newsweek.

Apart from this, various kinds of analysis were performed on the bony remains to determine the knights’ diets, their social structure, and hierarchy. Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of bone collagen were conducted to reveal dietary patterns typical of the Medieval social elite, according to the study. They concluded that the knights ate a diet rich in poultry, animal protein, and marine fish. The woman’s diet was also rich, again hinting that she was a knight, and not some servant, however, it was not as rich as that of the other, male knights. “We observed a lower level of protein consumption in the case of this woman, which could indicate lower status in the social group," explained Rissech.

Still, the scars and wounds found in her skeleton pointed to the fact that she did fight in a battle and was probably part of the Order of Knights. "She may have died in a manner very similar to that of male knights, and she was likely wearing some kind of armor or chain mail," said Rissech.

Although the conclusion about the woman being a warrior remains somewhat unclear, the study has opened intriguing doors into the history of this centuries-old military culture, promising more significant insights. "It was fascinating to see that, although the archaeology provided no direct evidence of their identities, our study helped to identify them and, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle—our results fit with historical sources describing the order and its function," Pérez-Ramallo said.

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books.

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books. Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia

Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: