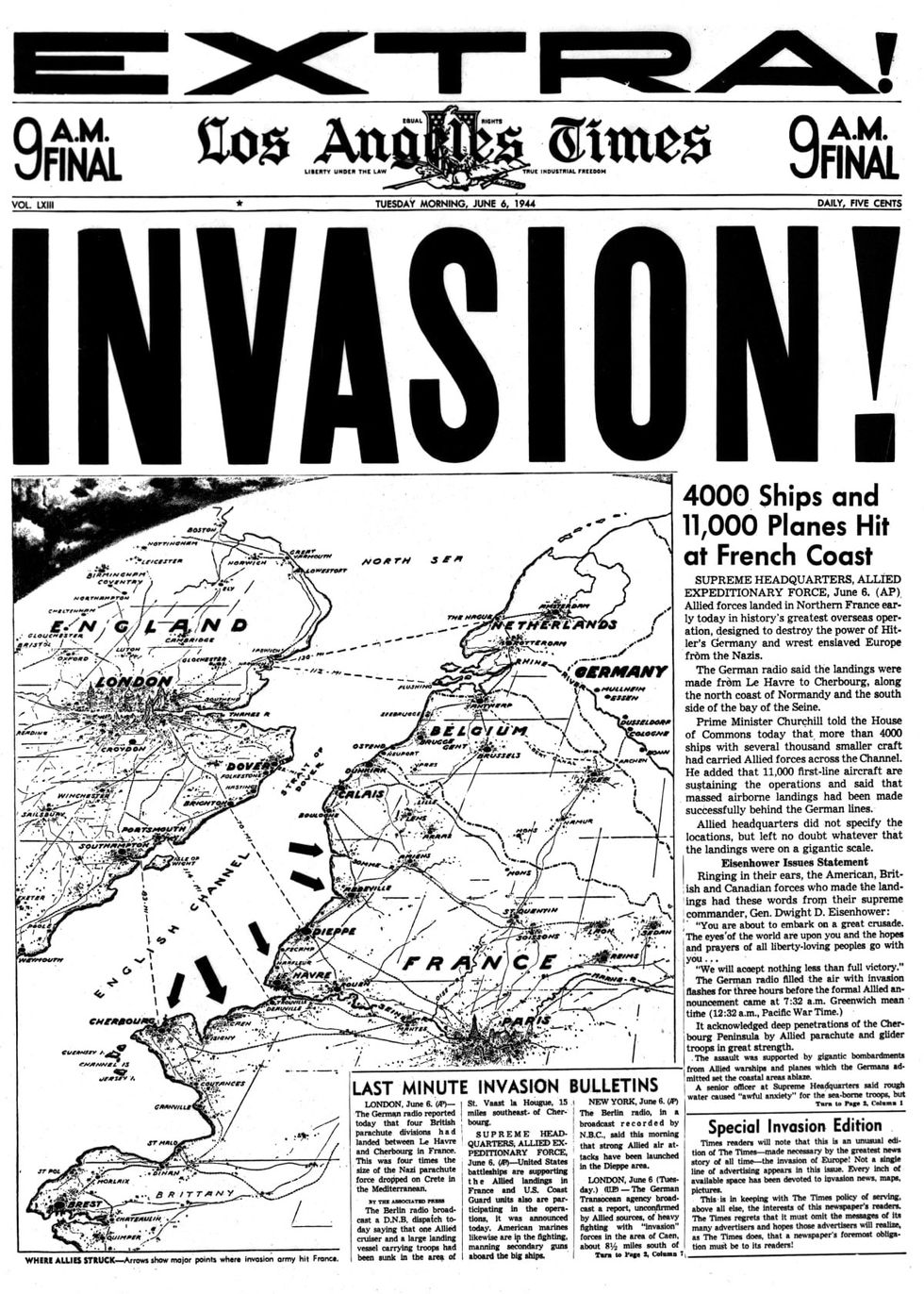

When Martha Gellhorn married Ernest Hemingway, they were prominent writers of the 20th century. But over time, their relationship turned sour, and the two became competitors from lovers. By early 1944, their marriage was already going through a rough phase. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Hemingway had taken Gellhorn’s job at Collier’s as a war correspondent for World War II. Undaunted, Martha pursued her passion and became the “only female correspondent to report the D-Day landings.”

Martha was the only woman reporter present on the beaches of Normandy when the Allied forces liberated France from the Nazis. At that time, no woman was permitted to report on the war. Despite Hemingway’s attempts to stop her from covering the war, she didn’t give up.

"It is necessary that I report on this war," Martha wrote in a rage-filled letter to the authorities. "I do not feel there is any need to beg as a favor for the right to serve as the eyes for millions of people in America who are desperately in need of seeing but cannot see for themselves," BBC quoted her letter.

To carry out her mission, Martha crafted a bizarre plan. The night before the invasion, she stowed herself inside a hospital ship by telling the military guards that she was there to interview nurses, according to the Military. Once inside, she locked herself in a bathroom and stayed put there until the ship was en route to France on June 6, 1944.

During the ship’s voyage to the French coast, Martha endured snipers, landmines, gunfire, and German warplanes. “Double and triple clap of gunfire,” Martha wrote in her diary, reported Smithsonian Magazine. “Unseen planes roar. Barrage balloons. Gun flashes. One close shell burst… Explosions jar the ship.”

During the next few days, Martha witnessed the ship’s harrowing conditions. The vessel had 422 hospital beds and six water ambulances to tend the wounded. Martha reached Omaha Beach and assisted the medics. “There was no time to talk; there was too much else to do,” she wrote in Collier's article “The Wounded Come Home.” She helped the wounded by lighting cigarettes, serving coffee, and lifting teacups to their bandaged mouths.

Dated August 5, 1944, the article recorded her risk-taking endeavor, “It will be hard to tell you of the wounded, there were so many of them,” she wrote. “They had to be fed, as most had not eaten for two days. They wanted water; the nurses and orderlies, working like demons, had to be found and called quickly to a bunk where a man suddenly and desperately needed attention.”

After her return, Martha was arrested by the British military police and was dispatched to a nurse training camp outside London. Undeterred, Martha continued her reportage of the war. She said she never expected any recognition or praise for her lionhearted adventures. She believed it was her job and made sure she did it right. “I followed the war wherever I could reach it,” Martha expressed, according to the National World War II Museum, “I had been sent to Europe to do my job, which was not to report the rear areas or the woman’s angle.”

Martha’s exceptional journalism stemmed not only from her unfaltering courage but also from her unique perspective. Rather than writing about war equipment or gunfire, she wrote about people who were affected by the war. She wrote about death and destruction. After the war, she continued reporting conflicts elsewhere. These toilsome years of witnessing wars took a toll on her health. Ovarian cancer eventually made it difficult for her to perform even basic tasks. So, she swallowed a cyanide pill and died at age 89 in February 1998. “For Gellhorn, I think it was all about making the world a better place,” said Maggie Hartley, director of public engagement at the National WWII Museum, “Whenever I give a talk, I like to include this quote by her: ‘There has to be a better way to run the world, and we had better see that we get it.'"

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books.

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books. Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia

Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: