The talks began in 1992. The grunge band Nirvana was in the middle of capitalizing on their success with their 1991 albumNevermind and their smash hit Gen X anthem "Smells Like Teen Spirit." They were the hottest rock group of the 1990s and trendsetters of the grunge movement in music at the time. For the recording of their next album, they talked to various music producers including Steve Albini, a notorious and controversial punk rocker turned producer/music engineer.

Albini was eager to work with the band, but on his own terms. He wrote out a pitch letter that laid out his philosophy and preferences to ensure that he and the band would be able to work comfortably together. The letter from beginning to end was a manifesto allowing freedom of musical artistry over technical wizardry mixed in with working class values.

He discusses how he imagined the record being recorded within a week’s time with no interference from office heads or labels getting folks in to remix and “sweeten” tracks. He wanted to record the authenticity of the band, even if there are some imperfections here and there, to “leave room for accidents or chaos,” to let the craftsmen (musicians) do their work with little interference or influence on his end since remixes and "sweetening" take too much time for little in return. He felt the "fixes" didn't really fix much. In turn, he wanted the album to speak for itself without letting uniformness and “perfection” get in the way of actual perfection.

Along with discussing possible locations to record the album, Albini got arguably to the root of the matter: money. Today, there are multiple stories regarding how music producers struggle to get fairly paid like other artists in the industry. In the 1990s, music producers often had more opportunities to get paid—such as points on the back end of record sales, royalties in perpetuity, and other such financial gains aside from a flat fee. Albini shied away from the usual demands of a “regular industry goon.”

@musicbyazuma How do music producers make money #musicindustry #musicbusiness #musicbusinesstips #musicbiz #musicproducer

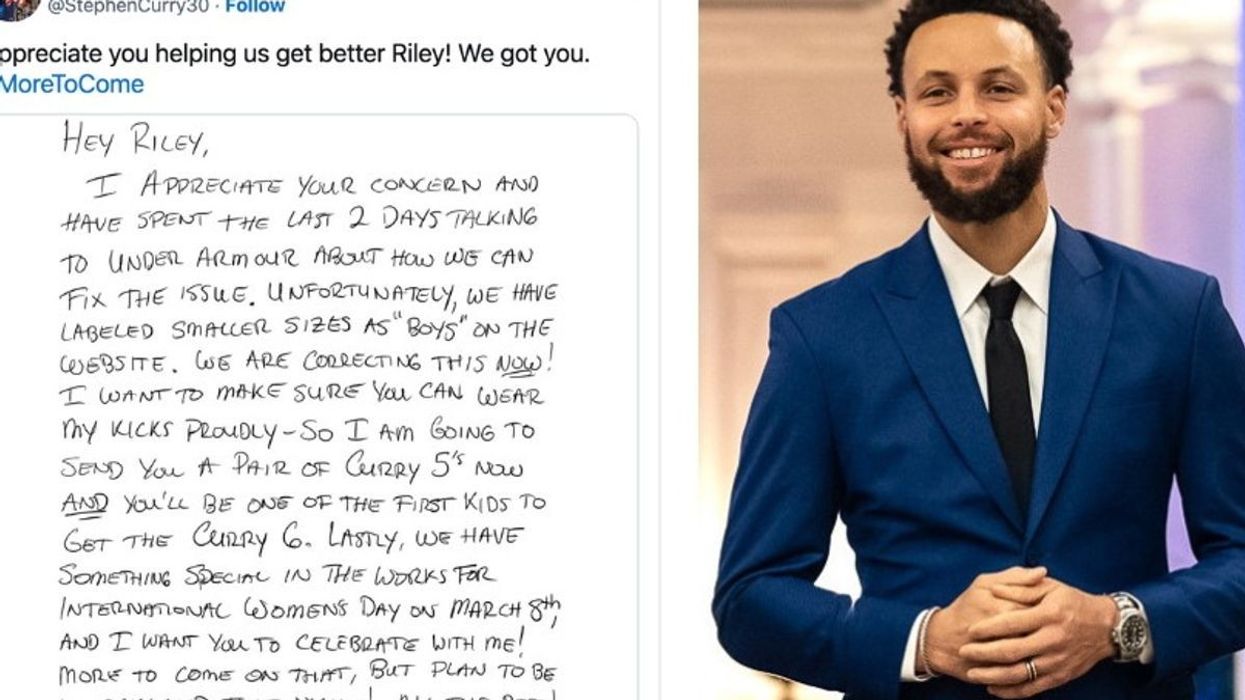

Albini wrote:

“I would like to be paid like a plumber: I do the job and you pay me what it’s worth. The record company will expect me to ask for a point or a point and a half. If we assume three million sales, that works out to 400,000 dollars or so. There’s no fucking way I would ever take that much money. I wouldn’t be able to sleep. I have to be comfortable with the amount of money you pay me, but it’s your money, and I insist that you be comfortable with it as well… I trust you guys to be fair to me and I know you must be familiar with what a regular industry goon would want. I will let you make the final decision about what I’m going to be paid. How much you choose to pay me will not affect my enthusiasm for the record.”

With that letter, Albini got the job.

He produced Nirvana’s third and unfortunately final album: In Utero. The final tracks panicked the record label, but they didn’t question the end results. The album debuted at number one on Billboard Top 200 when it was released, selling 4.2 million copies. It also produced two number one singles in the Alternative category: “Heart-Shaped Box” and “All Apologies.” It has since been re-released for 10th, 20th, and 30th anniversary editions.

The end result of a marriage of working class, get-it-done, measure-twice-cut-once, no fanciness-needed attitude mixed in with artistic vision was an album that has been celebrated and shared for generations. Just letting professionals and artists just do what they do can allow great work to happen.

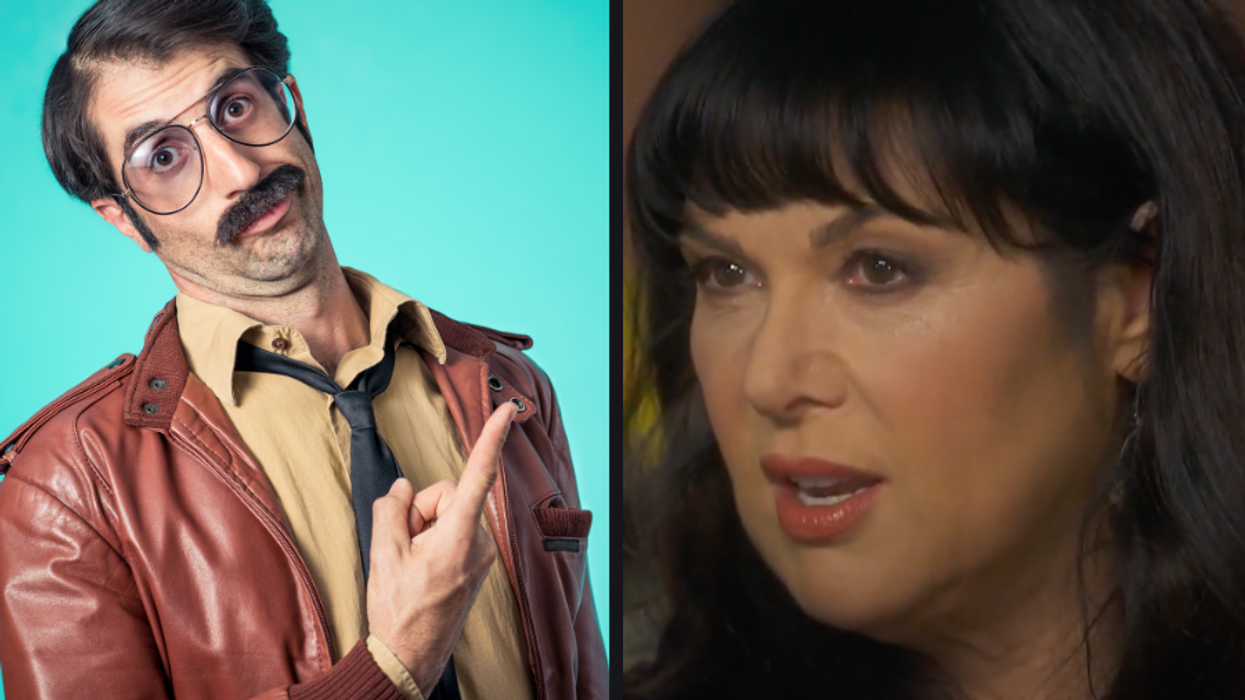

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper

Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

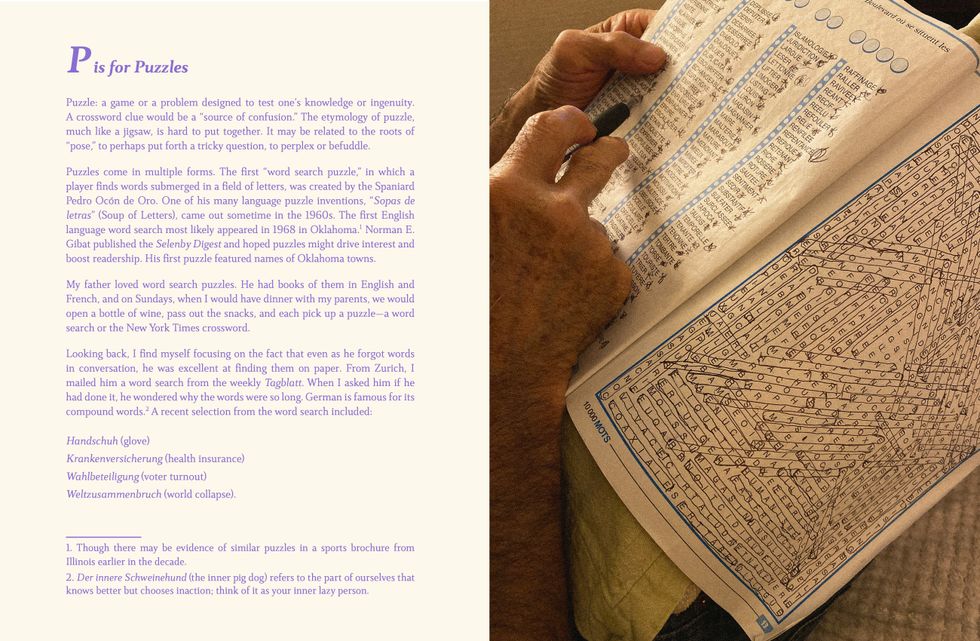

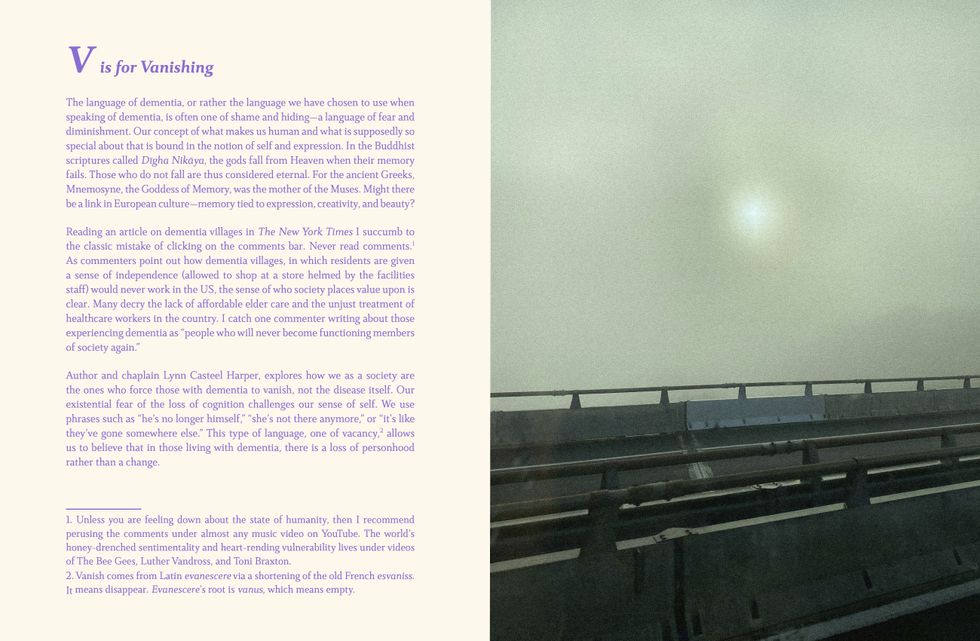

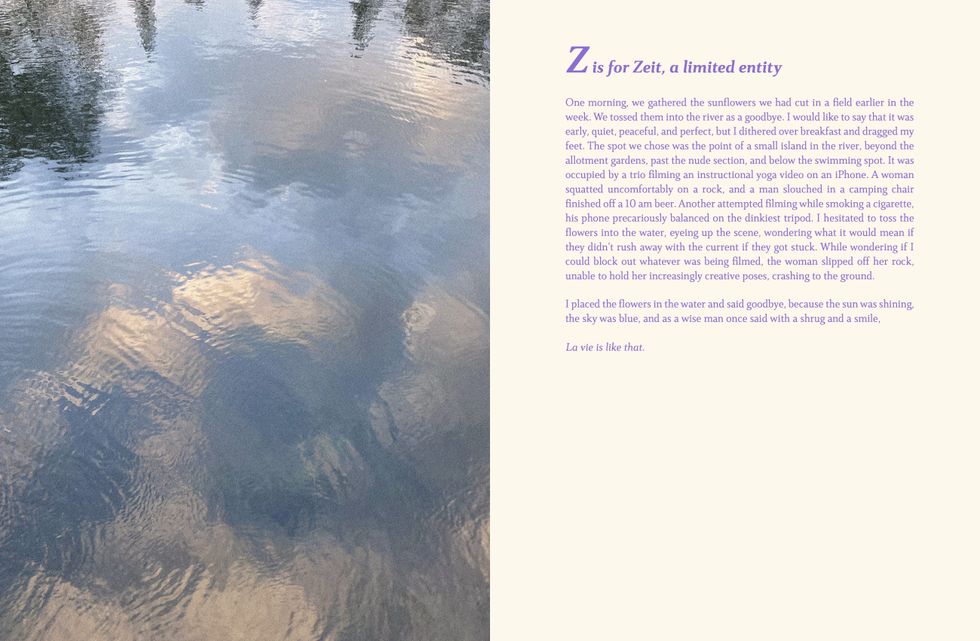

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

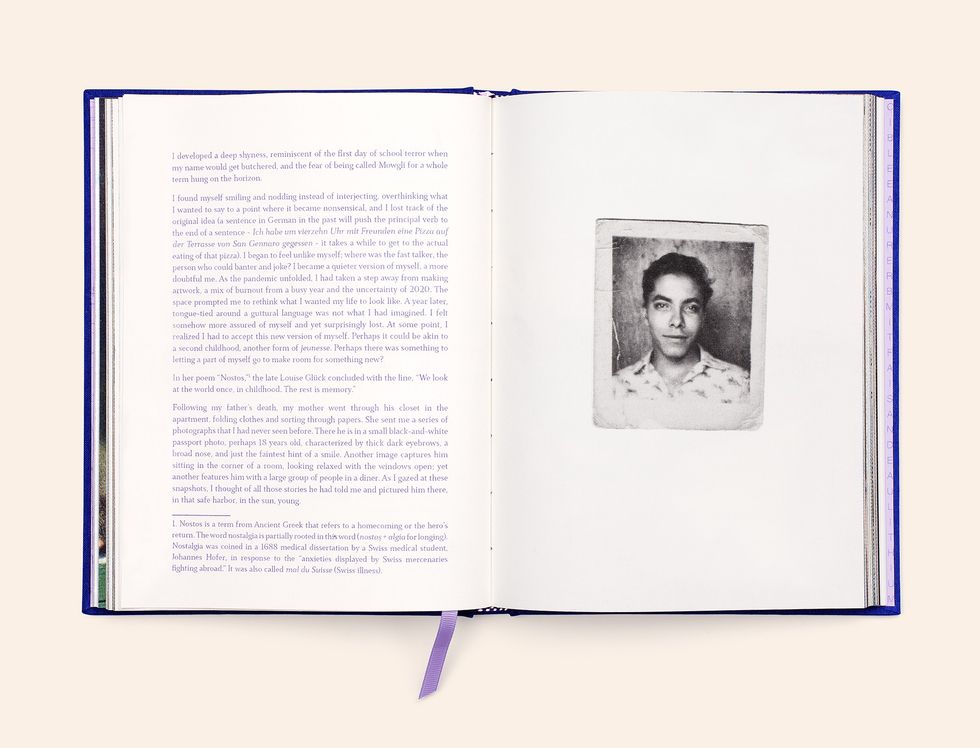

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like that featuring her father, Jean Gérard Benoît Duzant, as a young man.Magali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like that featuring her father, Jean Gérard Benoît Duzant, as a young man.Magali Duzant

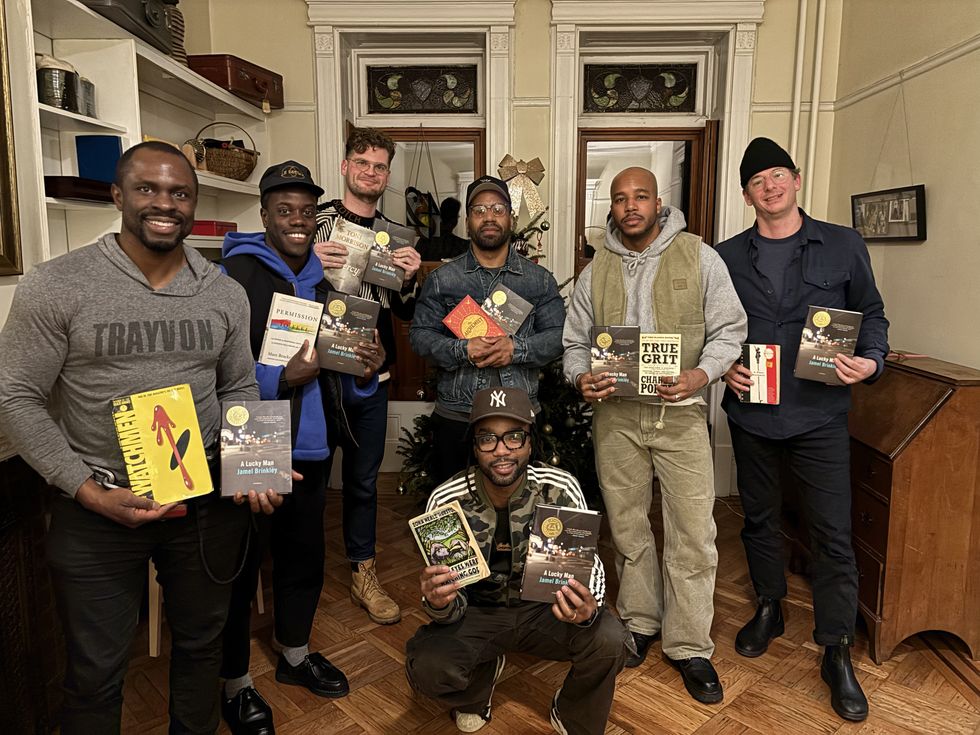

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel