Bright blue glasses rest on Wim Wenders’ face when I greet him at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York. He wears suspenders, one strap white and one black, with polka dots, that hold up chic, oversized trousers. Wenders, who’s most often known as the director of cinematic masterpieces–like 1984’s Paris, Texas, 1987’s Wings of Desire, and 1999’s Buena Vista Social Club, among many others–is also an accomplished photographer. His latest art exhibition, “Written Once,” which features images the director made in the 1970s and 1980s, opened at the Howard Greenberg Gallery on January 28 and runs until March 15.

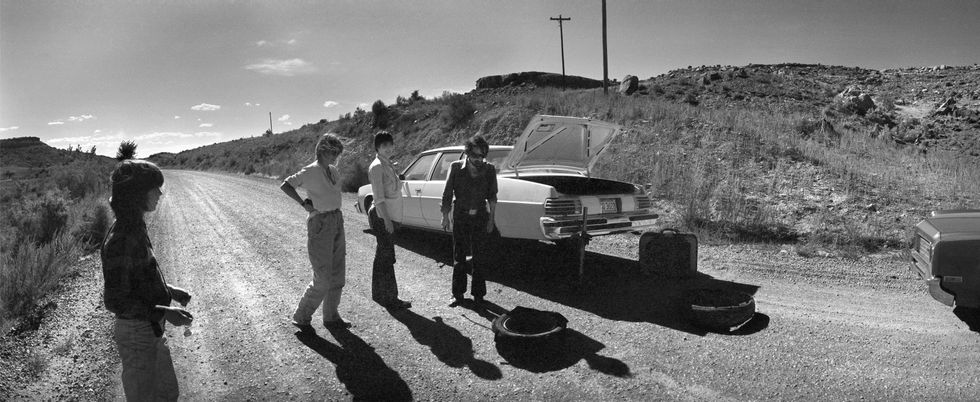

“Written Once” features images from two series previously published in Wenders’ books Once and Written in the West, some of which have never before been made into prints. From Once, elegantly grainy, soulful black and white images tell stories of Wenders’ time in the U.S.–in one image, Martin Scorsese repairs a flat tire in the middle of the desert; in another, the actor and musician John Lurie plants a powerful kiss on a companion. Written in the West sets the landscape of the American West alive in vibrant color, turning its grocery stores and gas stations into painterly landscapes.

Wenders and I sit in a room filled with images by master photographer Walker Evans, one of Wenders’ greatest inspirations. He jokes that he keeps getting distracted, but if he does I don't notice. For GOOD, we spoke about truth, place, storytelling, history, and self-reflection.

How did the show come together and how did you decide to put these series in conversation with each other?

[Gallerist] Howard [Greenberg] is strangely responsible. He came to my office, he went through all my drawers and got quite excited about some of the pictures. He chose the lesser-known pictures along with some exposed previously. He found some lost treasures and liked them, and just happened to be from these two series. He liked the idea that they're both books, that some of them were unknown, that I never printed them. I liked his eye and his choices. I was happy these pictures were reanimated and that I finally was able to print them. I'm more interested in the act of taking the picture than printing it. I've been taking photographs since I was a little boy but for 40 years of my life, I didn't print anything. I was happy I had the contact sheets. It was almost always more important for me that I took pictures, not that I did something with them afterwards. That changed with Written in the West, the first exhibition I had. Howard looked at my contact sheets and at my test prints [from that series], and said, “Oh, why didn't you use that one?” If somebody looks at my stuff from 40 years ago, I'm amazed by what they see in it and I say, “Oh yeah, you're right, not so bad. Why didn't I ever print it?”

Why were you more interested in the act of taking the picture than printing it?

Taking photographs for me is a very intense way of being and of looking. Photographs and my camera helped and guided me to travel, made me look more closely. My main profession is maybe traveler. In many ways, my camera feels like a recording instrument. It cannot just record a picture, but it also helps me understand a place and the story it tells me. It helps me to be somewhere and understand the light and the colors and see details, the history of a place, the history of the people [who] came through there, everything that we did to that place. For me, taking photographs is a way to be, to exist more in the moment and more intensely. Printing is not exactly in the moment. Printing is like going back and looking at something you experienced. I've always been interested in moving forward. Printing is almost like a nostalgic process. I'm not a nostalgic person, so I have to force myself, and I need somebody to tell me, “Wim, this picture, you better print it.”

What is it like to reflect on the work now decades later?

Photography is a medium where you're very intensely living in the now. I'm a photographer of places, much more than of people, even if there are people sometimes. It's really interesting to see who I was then, and who I was that saw these things, wanted to keep these moments and press the shutter. Today, if I was in the same place, I might take a very different picture. In a strange way, when I came into the gallery this morning, I encountered somebody I used to be, a young man very fascinated with America who lived and worked here in the 70s and 80s. I pretty clearly remember who that was, but I also realized I moved on. America has changed a lot. I realized that some of the places that interested me so much at the time have been either photographed to death, have disappeared, or were destroyed. The term “Americana” didn't exist when I made these pictures. It is now such a common word to describe a certain nostalgic feeling about America, but at the time I didn't feel it was a nostalgic journey. At the time it was truly sort of an exploration into the history of America. These places I show, especially in color, are historic places they talk about when they talk about American history. The West is an important part of American history. It's a country full of dreams, broken dreams, illusions and lost illusions. So to revisit them 40 years later, again, is another lost illusion [laughs]. Photographs are pretty solid in representing history. I love photography for the fact that it's so solid.

How do those ideas and your images live together?

These are all prints that are completely unmanipulated. What you see is what you get. What you see is what I saw. It's sort of an old fashioned idea of photography. Now the photo is no longer a witness of something that really happened, but a creation of something done with the help of a camera. There's Photoshop and all sorts of techniques. Looking at Walker Evans’s photographs, that's what he saw. My photos are from that tradition, like [photographer] Joel Meyerowitz, on the wall there. I love that man, so I'm in a strange way surrounded here by old friends. Walker Evans was my great hero when I was a young man growing up, maybe 15-16 years old and trying to do something with my camera. I realized you can do something so much more beautiful with it, not just photograph what's around you, your friends, family, and journeys–you could make photographs that were a statement. I'm completely overwhelmed that we're sitting here in a room with 15 Walker Evans photographs. For me, those are an expression of truthfulness, because it's more an attitude than a result. The result “truth” is always questionable, but the attitude producing something truthful is not questionable.

What does making a photograph teach you about how you want to make a film and vice versa?

My photography and my filmmaking have one thing in common: an extreme interest in place, in finding out its story, what part of history is reflected in it, what stories reverberate, and what I can read in it. My filmmaking is all place-driven. If I reach that state where I know that story--Berlin in Wings of Desire, the West in Paris, Texas–could not possibly have happened anywhere else, then I feel I've done justice to place and story, and I've told a story rooted in truth because the place and the story are linked in a necessary way. I need that.

For me, the truth of a story is very much linked to its place, and the characters need to be linked to a place. I like films that specifically take place somewhere else, where there is a history, a particular language, a tradition, habits–films that are linked to a certain region or countryside or to that city. I hate, and I often walk out of, movies when I realize they don't take place anywhere. A lot of movies take place nowhere and then you find out this is possibly Pittsburgh, but you know Pittsburgh and this is not Pittsburgh. A lot of movies are made not in the place where they're supposed to take place, but they're just where it pays off to shoot them because there's a tax rebate or something. I see “tax rebate” written big over many movies, and I can't stand realizing a place is phony. I don't want to watch a lookalike. I want to see the real thing. Why should I see a movie that takes place nowhere? Why should I believe the story of all these characters, that character sees something I know he can never, ever in his life, see there? I can't take it. I'm old fashioned. I need to believe that this is happening.

When you look at your work now, do you ever feel critical of yourself?

You cannot criticize the picture. You can criticize the attitude. I don't like all of these pictures there. Some are done sort of hastily, especially some of the black and white work. I didn't always think of myself as a photographer. I became one in the pictures I shot in America and the American West in preparation for Paris, Texas. I make a lot of journeys, only to take pictures, but not to make a movie, and then I make a lot of movies and I don't take a picture at the same time. It's two different attitudes. I can criticize an attitude, but I don't want to criticize the result. Some of my pictures are a little bit half-hearted I think now, but others are right on, and I'm happy I made them. I realized how much the attitude and being in the now creates the photo. I think the attitude of the photographer is visible in the shot, and that you can sometimes criticize. Sometimes it's a little bit superficial, sometimes it's just en passant. Some photographs are careless, others are profound.

The Zoo is also a great place for a date.

Photo by

The Zoo is also a great place for a date.

Photo by

Photo credit: National Basketball Association

Photo credit: National Basketball Association

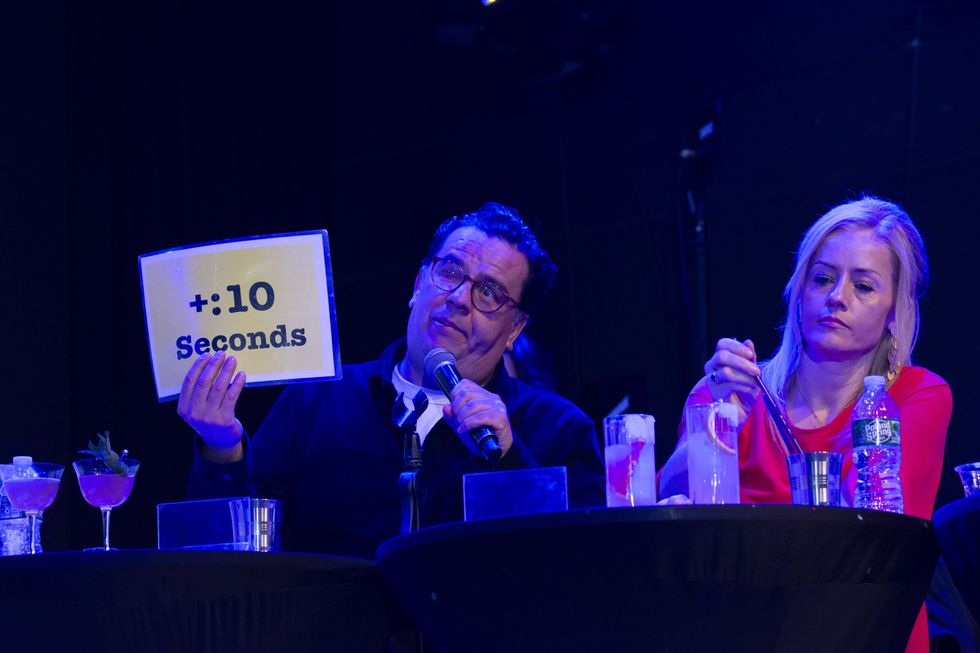

Competitors Sam Smagala, of the bar Joyface, and Miranda Midler, Head Bartender of Dear Irving's Broadway location, shake it off before Round 1 begins. Elyssa Goodman

Competitors Sam Smagala, of the bar Joyface, and Miranda Midler, Head Bartender of Dear Irving's Broadway location, shake it off before Round 1 begins. Elyssa Goodman Competitor Hope Rice of The Crane Club finishes up the final cocktail of her round, an Old Cuban, with a pour of G.H.Mumm Champagne. The Old Cuban is a drink created by legendary bartender Audrey Saunders. Elyssa Goodman

Competitor Hope Rice of The Crane Club finishes up the final cocktail of her round, an Old Cuban, with a pour of G.H.Mumm Champagne. The Old Cuban is a drink created by legendary bartender Audrey Saunders. Elyssa Goodman Competitor Ileana Hernandez just before her round begins. Ileana works at Greenwich Village restaurant Llama San.Elyssa Goodman

Competitor Ileana Hernandez just before her round begins. Ileana works at Greenwich Village restaurant Llama San.Elyssa Goodman Full of friends and industry professionals, the audience cheers for the annual New York Regional Speed Rack competition. Elyssa Goodman

Full of friends and industry professionals, the audience cheers for the annual New York Regional Speed Rack competition. Elyssa Goodman Competitor Rachel Prucha, of Mister Paradise and Hawksmoor, ready to take on her round.Elyssa Goodman

Competitor Rachel Prucha, of Mister Paradise and Hawksmoor, ready to take on her round.Elyssa Goodman Bartender Lana Epstein, of The Portrait Bar, wins Speed Rack's New York Regional competition. Friends and fellow competitors raise her up and offer bubbly to celebrate. Elyssa Goodman

Bartender Lana Epstein, of The Portrait Bar, wins Speed Rack's New York Regional competition. Friends and fellow competitors raise her up and offer bubbly to celebrate. Elyssa Goodman

Galentine's Day 2025Elyssa Goodman

Galentine's Day 2025Elyssa Goodman Galentine's goodiesElyssa Goodman

Galentine's goodiesElyssa Goodman

Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack

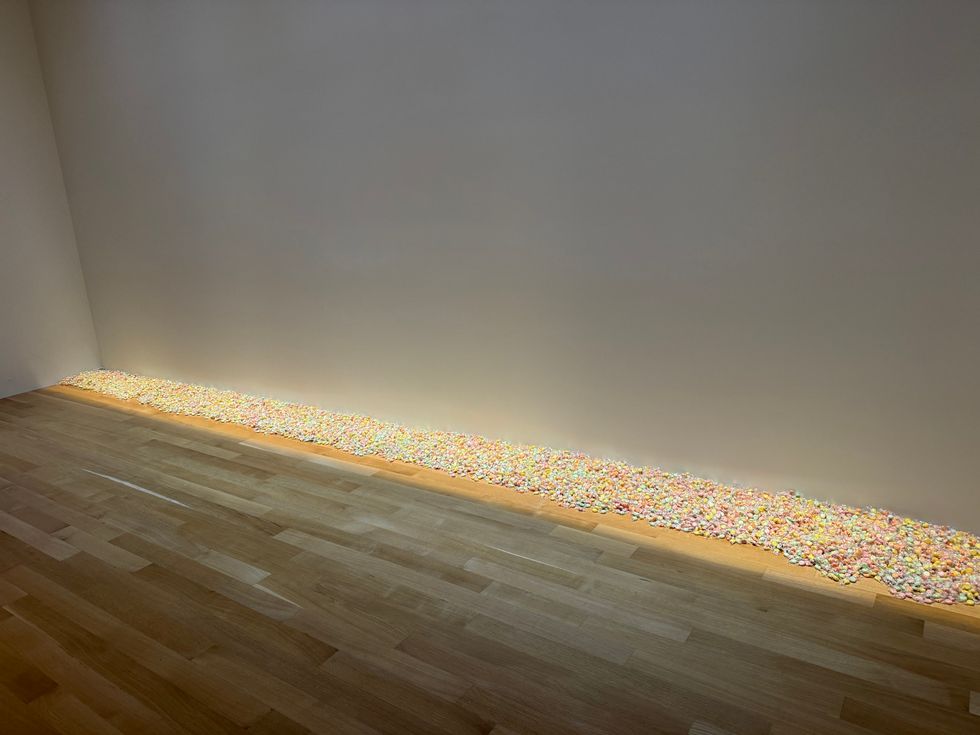

File:"Untitled" (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), National Portrait ...

File:"Untitled" (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), National Portrait ...