Fredrick Douglass was born into slavery in 1818. At the age of 10 he was given to the Auld family.

As a child, he worked as a house slave and was able to learn to read and write, and he attempted to teach his fellow slaves the same skills.

At the age of 15, he was given to Thomas Auld, a cruel man who beat and starved his slaves and thwarted any opportunity for them to practice their faith or to learn to read or write.

At the age of 20, after five years of working as a field hand, Douglass summed up the courage to run away. Armed with fake papers and a sailor-suit disguise, he escaped to the north with the help of Anne Murray, an emancipated woman who lived in Baltimore.

RELATED: After his old master wanted him back, the freed slave's response is a literary masterpiece

He settled in New Bedford in 1838 with his new wife Anne and began to share his story at abolitionist meetings and became a regular lecturer on the topic of slavery.

At the urging of abolitionist William Llyod Garrison, Douglass would write his first autobiography "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave," in 1845 and it would go on to become a bestseller in America and Europe.

In 1848, on the tenth anniversary of his enslavement, he wrote a letter to his former master, Thomas Auld, that was published in his newspaper "The North Star."

The letter is a beautifully written, harsh rebuke of both Auld and the institution of slavery. In the letter he speaks out about equality, the horrors of slavery, and asks Auld about the family members that he left back on the Auld estate.

The letter begins with Douglas refusing to write harsh words about his former master, but clearly letting him know how he feels.

"...I will not therefore manifest ill temper, by calling you hard names. I know you to be a man of some intelligence, and can readily determine the precise estimate which I entertain of your character. I may therefore indulge in language which may seem to others indirect and ambiguous, and yet be quite well understood by yourself."

He confessed to Auld the fear he felt the morning he ran away.

The hopes which I had treasured up for weeks of a safe and successful escape from your grasp, were powerfully confronted at this last hour by dark clouds of doubt and fear, making my person shake and my bosom to heave with the heavy contest between hope and fear. I have no words to describe to you the deep agony of soul which I experienced on that never-to-be-forgotten morning — for I left by daylight. I was making a leap in the dark.

RELATED: Twitter troll learns about the history of black cowboys the hard way

Douglass began to question his enslavement at a young age.

The very first mental effort that I now remember on my part, was an attempt to solve the mystery — why am I a slave? and with this question my youthful mind was troubled for many days, pressing upon me more heavily at times than others. When I saw the slave-driver whip a slave-woman, cut the blood out of her neck, and heard her piteous cries, I went away into the corner of the fence, wept and pondered over the mystery. I had, through some medium, I know not what, got some idea of God, the Creator of all mankind, the black and the white, and that he had made the blacks to serve the whites as slaves. How he could do this and be good, I could not tell. I was not satisfied with this theory, which made God responsible for slavery, for it pained me greatly, and I have wept over it long and often.

Then he realized why ...

I was puzzled with this question, till one night while sitting in the kitchen, I heard some of the old slaves talking of their parents having been stolen from Africa by white men, and were sold here as slaves. The whole mystery was solved at once.

He told Auld that his decision to run away was based on the fact that, as a black man, he was equal to him and needn't be subservient. A revolutionary claim to make in 1855.

I am myself; you are yourself; we are two distinct persons, equal persons. What you are, I am. You are a man, and so am I. God created both, and made us separate beings. I am not by nature bond to you, or you to me. Nature does not make your existence depend upon me, or mine to depend upon yours. I cannot walk upon your legs, or you upon mine. I cannot breathe for you, or you for me; I must breathe for myself, and you for yourself. We are distinct persons, and are each equally provided with faculties necessary to our individual existence. In leaving you, I took nothing but what belonged to me, and in no way lessened your means for obtaining an honest living. Your faculties remained yours, and mine became useful to their rightful owner.

He shared the joy he felt making his first dollar as a free man.

Three out of the ten years since I left you, I spent as a common laborer on the wharves of New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was there I earned my first free dollar. It was mine. I could spend it as I pleased. I could buy hams or herring with it, without asking any odds of anybody. That was a precious dollar to me. You remember when I used to make seven, or eight, or even nine dollars a week in Baltimore, you would take every cent of it from me every Saturday night, saying that I belonged to you, and my earnings also. I never liked this conduct on your part—to say the best, I thought it a little mean. I would not have served you so.

Douglas soon began to work for Garrison who encouraged him to speak out about the horrors of slavery, including those inflicted on him by Auld.

After remaining in New Bedford for three years, I met with William Lloyd Garrison, a person of whom you have possibly heard, as he is pretty generally known among slaveholders. He put it into my head that I might make myself serviceable to the cause of the slave, by devoting a portion of my time to telling my own sorrows, and those of other slaves, which had come under my observation. This was the commencement of a higher state of existence than any to which I had ever aspired. I was thrown into society the most pure, enlightened, and benevolent, that the country affords. Among these I have never forgotten you, but have invariably made you the topic of conversation — thus giving you all the notoriety I could do. I need not tell you that the opinion formed of you in these circles is far from being favorable. They have little respect for your honesty, and less for your religion.

After having his own children, the terror of slavery seemed to intensify in Douglas' eyes.

There are no slaveholders here to rend my heart by snatching them from my arms, or blast a mother's dearest hopes by tearing them from her bosom. These dear children are ours — not to work up into rice, sugar, and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel — to train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can, to make them useful to the world and to themselves. Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control.

He then asks Auld if he still owns his three sisters and grandmother.

If my grandmother be still alive, she is of no service to you, for by this time she must be nearly eighty years old — too old to be cared for by one to whom she has ceased to be of service; send her to me at Rochester, or bring her to Philadelphia, and it shall be the crowning happiness of my life to take care of her in her old age. Oh! she was to me a mother and a father, so far as hard toil for my comfort could make her such. Send me my grandmother! that I may watch over and take care of her in her old age.

In the most provocative part of the latter, Douglass asks Auld what if would be like for him if the tables had been turned.

How, let me ask, would you look upon me, were I, some dark night, in company with a band of hardened villains, to enter the precincts of your elegant dwelling, and seize the person of your own lovely daughter, Amanda, and carry her off from your family, friends, and all the loved ones of her youth — make her my slave — compel her to work, and I take her wages — place her name on my ledger as property — disregard her personal rights — fetter the powers of her immortal soul by denying her the right and privilege of learning to read and write—feed her coarsely—clothe her scantily, and whip her on the naked back occasionally; more, and still more horrible, leave her unprotected — a degraded victim to the brutal lust of fiendish overseers, who would pollute, blight, and blast her fair soul—rob her of all dignity — destroy her virtue, and annihilate in her person all the graces that adorn the character of virtuous womanhood? I ask, how would you regard me, if such were my conduct?

He concludes the letter by telling Auld he will use his experience as his slave to attack the institution itself.

I intend to make use of you as a weapon with which to assail the system of slavery—as a means of concentrating public attention on the system, and deepening the horror of trafficking in the souls and bodies of men. ... In doing this, I entertain no malice toward you personally. There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other.

I am your fellow-man, but not your slave.

Frederick Douglass

You can read the entire letter here.

Douglass would later learn that when his grandmother was deemed too old to work, she was given to another owner and was eventually "turned out" or sent to live by herself in a hut in the woods.

In 1877, 14 years after the emancipation proclamation, Douglass met with an aging Auld and they could't hold back the tears. After the meeting, the two parted as friends.

"Frederick," said Auld, "I always knew you were too smart to be a slave, and had I been in your place, I should have done as you did."

"I did not run away from you," Douglass replied. "I ran away from slavery."

More on Good.is

The Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress ...

The manumission of Frederick Douglass | Gilder Lehrman Institute of ...

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: Chapters VII ... - SparkNotes

Letter to His Old Master - Story of the Week

FREDERICK DOUGLASS AND THOMAS AULD: RECONSIDERING ...

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: Chapter XI ... - SparkNotes

from The Lost Letters of Frederick Douglass by Evie Shockley ...

Frederick Douglass - Wikipedia

Frederick Douglass's Emotional Meeting With His Former Slave Master

Letter to Thomas Auld (September 3, 1848) | The Gilder Lehrman ...

After his old master wanted him back, the freed slave’s response is a literary masterpiece. - GOOD

Pexels | Photo by Andrea Piacquadio

Pexels | Photo by Andrea Piacquadio

An Atlantic grey seal looking at the camera underwater. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Mark Chivers)

An Atlantic grey seal looking at the camera underwater. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Mark Chivers) A grey seal swims up to a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Huw Thomas)

A grey seal swims up to a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Huw Thomas) A Grey seal nibbles at the hood of a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Bernard Radvaner)

A Grey seal nibbles at the hood of a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Bernard Radvaner)

Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen co-host the HFC Austin Brain Health Dinner on September 30, 2023, in Austin, Texas. (Photo by Rick Kern/Getty Images for Hilarity for Charity)

Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen co-host the HFC Austin Brain Health Dinner on September 30, 2023, in Austin, Texas. (Photo by Rick Kern/Getty Images for Hilarity for Charity) Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen attend the 95th Annual Academy Awards on March 12, 2023 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Arturo Holmes/Getty Images )

Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen attend the 95th Annual Academy Awards on March 12, 2023 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Arturo Holmes/Getty Images ) Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |  Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |

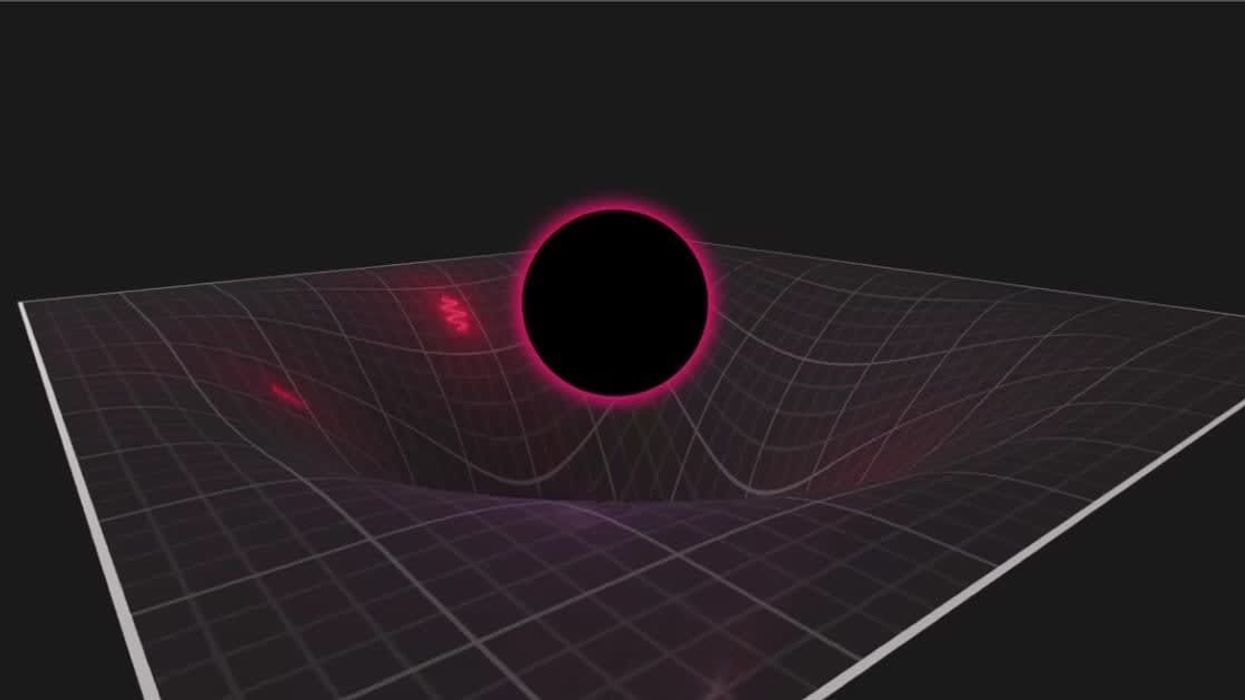

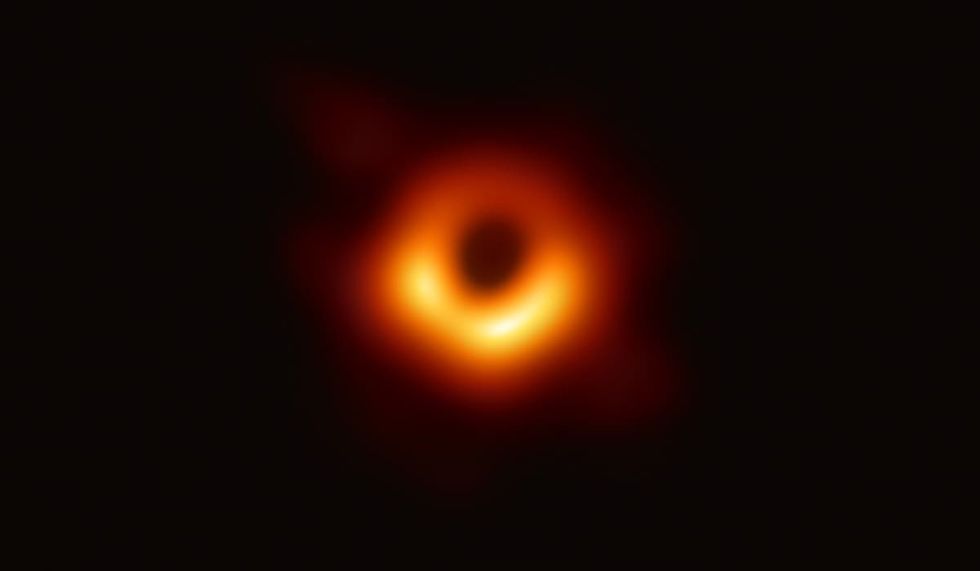

Image Source: In this handout photo provided by the National Science Foundation, the Event Horizon Telescope captures a black hole at the center of galaxy M87 in an image released on April 10, 2019. (National Science Foundation via Getty Images)

Image Source: In this handout photo provided by the National Science Foundation, the Event Horizon Telescope captures a black hole at the center of galaxy M87 in an image released on April 10, 2019. (National Science Foundation via Getty Images)

Representational Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich

Representational Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kampus Production

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kampus Production

Image Source: Destroyed vehicles lie near the rubble after the earthquake and tsunami devastated the area on March 16, 2011, in Minamisanriku, Japan. The 9.0 magnitude strong earthquake struck offshore on March 11 at 2:46 pm local time, triggering a tsunami wave of up to ten meters which engulfed large parts of north-eastern Japan. (Photo by Chris McGrath/Getty Images)

Image Source: Destroyed vehicles lie near the rubble after the earthquake and tsunami devastated the area on March 16, 2011, in Minamisanriku, Japan. The 9.0 magnitude strong earthquake struck offshore on March 11 at 2:46 pm local time, triggering a tsunami wave of up to ten meters which engulfed large parts of north-eastern Japan. (Photo by Chris McGrath/Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay Representative Image Source: Pexels | Stuart Pritchards

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Stuart Pritchards

Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the 2009 American Music Awards at Nokia Theatre L.A. Live on November 22, 2009 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Jeffrey Mayer/WireImage)

Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the 2009 American Music Awards at Nokia Theatre L.A. Live on November 22, 2009 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Jeffrey Mayer/WireImage) Image Source: Keith Urban and Nicole Kidman attend The 2024 Met Gala on May 06, 2024 in New York City. (Photo by John Shearer/WireImage)

Image Source: Keith Urban and Nicole Kidman attend The 2024 Met Gala on May 06, 2024 in New York City. (Photo by John Shearer/WireImage) Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the Oscars on February 24, 2013 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Jeff Vespa/WireImage)

Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the Oscars on February 24, 2013 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Jeff Vespa/WireImage)

Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu

Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu

Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu Representative Image Source: Pexels | Djordje Vezilic

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Djordje Vezilic Representative Image Source: Pexels | Fauxels

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Fauxels